Ellis: What Patagonia Got Wrong

I’ve admired the Patagonia brand for a long time – all the way back to college when the cool kids could afford it and I couldn’t.

Dare I say that very few of those college students realized the eco-conscious mission that Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard built his company on. This was North Mississippi in the mid-2000s, after all. Those kids weren’t eco-warriors. Some wanted to flaunt their family’s wealth. Some just wanted to lead others to believe they had it, too.

The Patagonia jacket was a key piece of a college kid’s old money aesthetic. Guys would throw it over a Lacoste polo. Girls would wear it on top of a T-shirt sporting the letters of their $900-a-month sorority.

On days when it was chilly, the rich kids would wear Rainbow sandals and short shorts below the waist and their Greek uniform above it. They would traipse from the commuter parking lot and the BMW or Mercedes their parents bought them all the way across campus to the Trent Lott Leadership Institute.

I had the short shorts and flip-flops, but walked from my sophomore dorm to the journalism building in a Columbia jacket – every bit as functional, but a fraction of the price.

Trust me on this, though: I wasn’t principled as a 20-year-old. I just didn’t have the money for a more expensive jacket.

We’ve all gotten older. The kids with family money and the posers are grown up now. I no longer reside in the little self-contained garden of envy that is a college campus, and yet Patagonia remains a status symbol.

You’re sure to spot the Patagonia brand on ritzy ski resorts and the Aspen Ideas Festival. Some of the adults wearing Patagonia want to flaunt their sustainability bona fides. Some just want others to believe they have it, too.

You don’t have to be an environmentalist to purchase a Patagonia jacket off the rack. Yet, if a retail consumer buys one of these jackets, it’s not likely to end up in a landfill. That’s because of the brand’s perceived value as much as the imagined contract a purchaser makes with planet Earth upon receipt.

As it happens, the products' worth and eco cred also combine to make Patagonia an immaculate promo option. If a corporate worker or conference attendee is gifted one of these jackets free of charge, it’s still not likely to end up in a landfill.

It’s a positive for the promo industry, full stop, that Patagonia has reversed its course and will again offer co-branding on its products, as PPAI Media first reported on Saturday. But the company has seemingly never understood why it’s valuable in this market and why its two-year absence was a slight against its own mission.

I see it this way: Patagonia has marketed its products not only as eco-friendly, but also as high worth. Whether there is a secondary logo on a jacket or not – and perhaps because there is the right secondary logo – people will keep and use these products.

Two for the price of one. #FirstClassPromo stays undefeated. https://t.co/JI4epnSRSs pic.twitter.com/YleiGznBX5

— Josh Ellis (@JoshPPAI) February 24, 2023

I’ve started conducting a little experiment that I invite every reader to join me in. When you board your next airline flight, look around first class and take note of all of the promo products you see. They're everywhere. People who are wealthy enough have no compunction about corporate brands they are proud to wear.

And just as on a college campus, people who wish they had more will be happy to make it look like they have plenty. They will wear their promo Patagonia jacket in off-hours. They will wear it after they’ve left one company for another that hasn’t given them a status symbol jacket.

Recent PPAI research revealed that consumers view promotional products positively during times of economic hardship. We pointed the survey at the real possibility of an upcoming recession, but it also sheds light on how anyone who has less than someone else may feel about quality retail branded products.

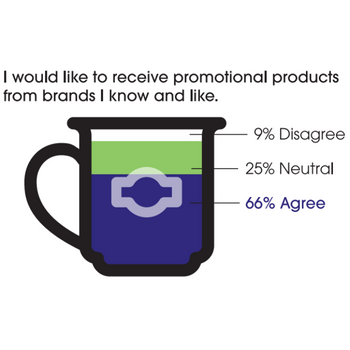

Only 9% of people say they would not like to receive promotional products from brands they know and like. Less than 20% say quantity is more important than quality when it comes to promo.

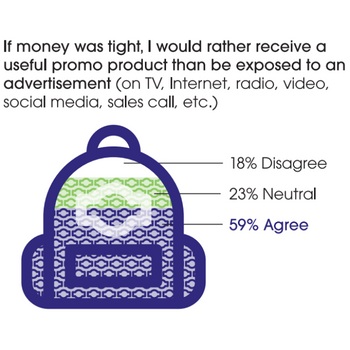

And likewise, less than 20% say they would rather be exposed to another form of advertising than receive a useful promotional product – i.e., a nice warm jacket or a warm nice jacket, depending on your personal motivation.

People keep products they want to use, and they’re more likely to want to use them if they are proud of them. With any campaign, today's savvy distributors are asking clients whether they believe a promotional product is useful and likely to be kept by its intended audience. If not, they suggest an appropriate alternative product or imprint location.

No matter where the secondary logo is placed, Patagonia’s standing as a status symbol makes its co-branded promotional products sustainable in a unique way. Its products’ perceived value are so high that people who have already been gifted a good-looking, long-lasting Patagonia product should be less likely to purchase a new jacket, beanie or bag of lesser quality. That, in and of itself, is a positive sustainability step for the world.

Anything that could make a consumer less likely to consume more is a positive sustainability step for the world.

Secondary logo be damned, someone who receives a high-quality item is not as likely to seek a replacement, or a second or third replacement as the lesser products wear out. The negative environmental effects of fast fashion have been well documented.

Patagonia is most certainly not the only high-quality jacket available through promotional products suppliers. There are many, many more options, and distributors have found them for clients in the last two years.

Still, evocative brands will always matter. It’s a mistake for any retail brand to shrink from – or not recognize – its own power for good.

Hopefully Patagonia is now in for the long haul.