PFAS: The Chemical Dilemma

There’s a regulatory issue on the horizon that practically every company operating in the promotional merchandise market is going to have to deal with. And that horizon isn’t evenly distributed. For some, they’ve already reached it, and for others it’s in the short- or medium-term distance. But it’s coming, and most of us are going to have to contend with it, one way or another.

There are more than 9,000 perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (aka PFAS) in use today in myriad products. Due to the strength of their carbon-fluorine bonds, they are persistent, bio-accumulative “forever chemicals,” and some have been shown to have multiple, adverse effects on human health. Governments at the state and federal level, and around the world, are enacting regulations controlling or prohibiting their use.

These rules apply to different product categories, follow different schedules, require different testing and mandate different responses. In short, it’s very confusing.

“This subject is really for the chemists,” says Rick Brenner, MAS+, president and CEO of Product Safety Advisors. “But all of our industry is going to have to deal with it at an administrative level. What test do I need to tell me it’s OK? That sort of thing. Nobody’s going to become an expert in it, but we need to understand what it means for our businesses.”

The PFAS Origin Story

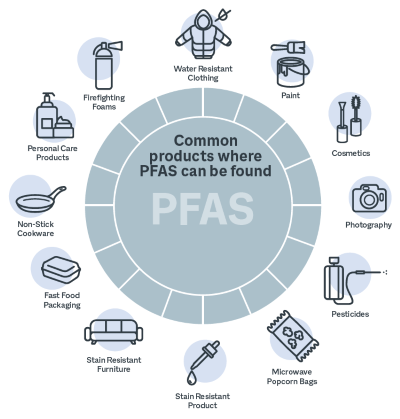

First discovered in the 1930s, PFAS chemistry has been appearing in consumer and industrial products since the 1940s. The substances have been incorporated in a broad range of goods to provide water- and stain-resistant properties, nonstick surfaces, flexibility and durability, and other capabilities. Think Teflon and Scotchgard.

Common consumer products that contain PFAS include grease-resistant paper, fast food containers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes and candy wrappers. PFAS can also be found in:

- Nonstick cookware.

- Stain-resistant coatings used in upholstery and fabrics.

- Water-resistant clothing.

- Cleaning products.

- Personal care products like shampoo and dental floss.

- Cosmetics like nail polish and eye makeup.

- Paints, varnishes and sealants.

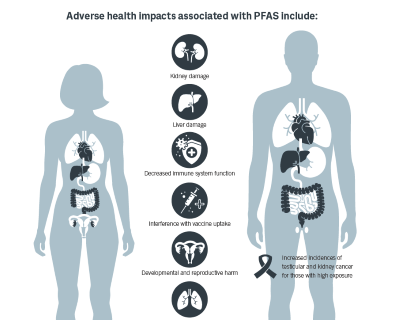

The first clues that PFAS may have adverse health effects came in the 1970s, when studies found the chemicals in the blood of occupationally exposed workers. PFAS was found in the blood of the general population in the 1990s. That discovery led to greater awareness of the chemicals and concerns over their presence in the environment and humans, as well as potential health impacts.

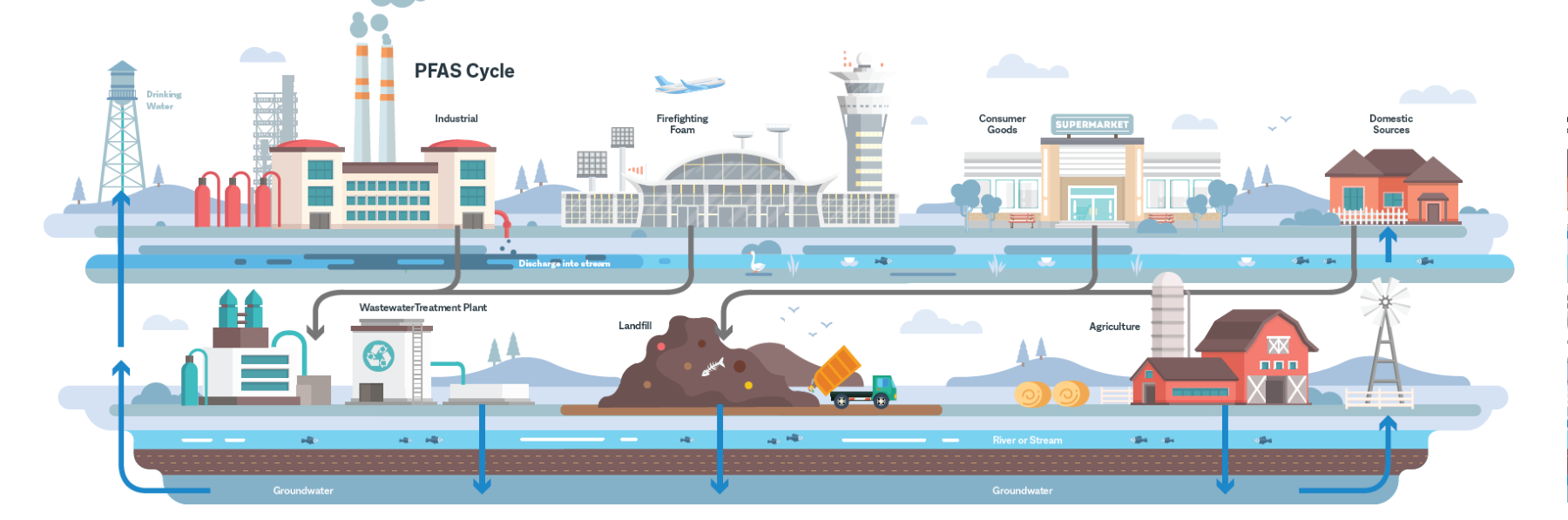

Widespread documentation of environmental contamination didn’t happen until the early 2000s. PFAS chemicals can pollute sources of drinking water and the environment in multiple ways, through washing and disposal in landfills and incinerators. The chemicals have been found in sediments, surface and groundwater and wildlife. Some have been found in places throughout the world far beyond where the chemicals were initially used or manufactured.

Legislation in New York enacting certain PFAS prohibitions notes, “mounting research has linked well-known PFAS compounds such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) to kidney and testicular cancer and communities with PFAS contaminated water have been shown to suffer serious medical effects.”

The same bill cites research from the John Wood Group, an engineering and consulting firm, that says, “PFASs are very persistent in the environment, and some are highly soluble and mobile. Documented evidence has shown that PFASs emitted to soil can readily move into groundwater and be transported well beyond the original contamination source.”

The Regulatory Landscape

PFAS chemicals are coming under regulatory scrutiny from all corners: Numerous states have enacted laws and regulations controlling or prohibiting the chemicals’ use or managing human exposure, the Environmental Protection Agency is considering new rules, and in February, the European Union proposed a ban on the manufacture, use and selling of goods containing PFAS in the common market.

States’ focus on PFAS has typically centered on various product categories, namely:

- Food packaging.

- Cosmetics or personal care products.

- Children’s products.

- Textiles.

- Fabric, carpets or rugs, and upholstery.

- Fish and deer meat harvested from select waterways and areas.

How this activity affects the promotional products industry varies. Recent legislation of particular note to the promo industry includes bans on PFAS use in apparel that passed in New York and California. These prohibitions go into effect on December 31, 2023, and January 1, 2025, respectively.

But by no means are these the only regulations instituted at the state level that will impact the industry. Seventeen states have one or more regulations governing PFAS use, while four more have bills in consideration. A law went into effect in Maine on January 1 that mandates notifying the state of any product being sold in the state that had intentionally added PFAS.

Complicating efforts to comply with these laws, the prohibitions not only cover different product categories, but differ on timetables, how they measure PFAS and which chemicals they apply to – remember, there are more than 9,000 PFAS in use.

Several federal agencies are also moving on PFAS. Among them is the Environmental Protection Agency, which in 2021 established a strategic roadmap to take specific actions and commit to new policies to protect public health and the environment, and to hold polluters accountable. In September it proposed designating two PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, as hazardous due to “significant evidence” that they present “substantial danger to human health or welfare or the environment.”

Another federal agency examining the impact of PFAS on public health is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which has several ongoing reviews of PFAS in food and food containers.

“There is no current federal regulation on PFAS in any consumer product,” says Brenner. “It’s not like Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, where there’s a specific threshold that you can’t have more than so much lead and lead in the substrate of any product, or so much lead in the surface coating. There’s nothing like that for PFAS at the federal level yet.”

In fact, he adds, if we go back to the way that lead was regulated in the U.S., it’s a very similar situation to what’s going on now with PFAS.

“In the summer of 2007, there were millions and millions of Barbie dolls and other Chinese toys that were recalled. It is referred to as the ‘summer of recalls.’ As a result, a number of states started passing lead regulations – and none of them were harmonized with another, and it became very challenging,” Brenner says. “What can we do when there are different regulations in different states, and they have different definitions of what’s covered and what’s not covered?”

In August 2008, the CPSIA was signed into law. One of its provisions was that all state consumer product safety regulations that had been passed subsequent to 1986 were preempted. With the federal laws in place, companies didn’t have to worry about what state they were dealing with.

Brenner says, “It was a benefit to all of us in the industry because all of a sudden we had a standard that applied everywhere. We’ve got the same situation now, and that’s the issue. You have all of these states passing legislation right now about PFAS, and they’re not harmonized.”

Without federal standards, the simplest thing for industry companies to do is to find the strictest state standard that goes into effect on the earliest date and apply it to their product lines and production methods.

The European Union’s proposed ban on PFAS is the bloc’s largest chemical restriction to date. If adopted, the measure would prohibit the manufacture, use and importation of PFAS on their own, as well as the manufacture and importation of products and substances that contain PFAS. Companies would potentially have to redesign a range of products intended for the EU market.

Adding another wrinkle to the regulatory landscape stems from children’s products. State regulators pay close attention to PFAS in children’s products, prompting more stringent restrictions. Seven states currently have laws on the books regarding PFAS chemicals in children’s or juvenile products. Six more states have proposed regulations in 2022 and 2023.

What Does This Mean For Promo?

For promotional products companies, whether or not their business is subject to current regulations related to PFAS, the wise move today is to evaluate production methods and products to determine if they use or contain these chemicals and are subject to potential risks.

Industry companies are already moving to manage the PFAS issue. In December, 3M, which participates in the promotional products industry as a supplier through its 3M Promotional Markets division, announced that it would exit PFAS manufacturing by the end of 2025.

“This potentially has a huge impact on the promo industry as it is everywhere,” says Chris Pearson, MAS, vice president of compliance and Asia operations at supplier Spector & Co. “Even the largest manufacturers have been using PFAS for years for waterproofing and stain resistance. It is also found out in the world because of this, so trace amounts are everywhere.”

Electronics and soft goods suppliers are especially vulnerable to these regulations, he adds.

“It takes a long time to engineer these out with a safe alternative,” Pearson says. “We used to use a different version and that was the solution, but now we realize that the substitute was equally as bad as the original. Without a loss of properties and features, this is very difficult to remove.”

As has always been the way in every regulatory shift, compliance is driven by the largest customers. Industry distributors selling to smaller businesses are likely to never have a problem. Distributors who deal with companies like Nestlé, General Mills and McDonald’s, etc., will have to be prepared, because those are the type of customers who are going to be unable to buy anything without conclusive proof that the goods they’re purchasing don’t contain proscribed PFAS chemicals. To be successful, these distributors need their suppliers to be prepared.

“Suppliers in this industry are the ones that need to deal with this,” says Brenner. “They’re the ones that need to understand what’s in their products and whether or not PFAS is part of it. That’s going to be a matter of them contacting their testing lab, getting an education, reviewing their product categories, reviewing their products and developing a strategy, because the distributors in the industry are going to be asking, ‘Is there PFAS in it?’”

Brenner adds, “It’s really challenging. I don’t think a distributor who’s trying to sell all day long, they don’t have time to be on the phone for three hours to get answers like this. They’re going to rely on the suppliers to be vetting their sources and understanding what’s in the products they’re selling. It’s going to be a big challenge for suppliers because they need to know what’s in everything they make.”

Test, Test, Test

The regulatory impact on the promo industry has the potential to be far reaching. PFAS’ ubiquity means it’s likely to found in a wide swath of the industry’s goods.

“Take PFOA, one of the chemicals on California’s list,” says Brenner. “The question is, what’s PFOA in? Well, if you tried to test your products for every PFAS, it would be far too expensive. Different labs have different strategies, but basically the approach is to start with testing for either total fluorine or total organic fluorine under the basis that if it doesn’t have that in it, it can’t have PFAS in it because every PFAS bond is carbon and fluorine.”

Pearson says, “Promo companies need to start testing and certifying their supply chains to ensure there are no intentionally added PFAS’ to their products. The companies with more robust testing and compliance programs already are doing this.”

Promotional products companies can logo, source and distribute any consumer product, and should be cautious when using categories with the potential to contain PFAS.

“Be aware of the product categories that are at higher risk for containing these chemicals,” says Karolyn Helda, managing director at supply chain solutions provider Qima. “Know your suppliers and what is in your product. The product's Bill of Materials and Bill of Substances can be reviewed to determine if PFAS are added. However, factories may not be willing to provide this information, and therefore it will be up to the promo industry company to conduct testing to monitor their products. A good option is to test suspect materials, such as a coating on a textile, for total organic fluorine.”

Helda notes that alternatives to PFAS are coming onto the market – hydrocarbons and waxes are being adopted by outdoor brands for use in textiles; cellulose-based alternatives, biopolymers and biowaxes are being used in food packaging; and the cookware industry offers ceramic and hard-anodized options. But even as these come available, testing and scrutiny will remain important.

“Chemical alternatives to PFAS are being developed and studied,” says Helda. “But like with any new chemical, companies need to do their homework on the safety of the alternative before employing it for use on their products."

What’s Next?

It’s not yet clear whether the industry will get federal regulations harmonizing rules regarding PFAS across the country like it did with CPSIA. Regardless, promo companies need a strategy.

“This is coming, and you need to be aware of it,” says Brenner. “There are countless products that have PFAS that we’re selling every day."

“If you’re a distributor, you need to be asking questions of your suppliers, and suppliers need to study the issue and understand where and why these chemicals are used. The best advice is to be aware of them and to try to get an education on how they are used and where they are in our inventories.”

Industry businesses may or may not be affected by the consumer product regulations related to PFAS. But because the chemicals are so prevalent in goods today, prudent companies should evaluate their potential risk now to determine if PFAS can be found in their products or production methods.

Promo companies also have educational opportunities to available to them, as PPAI’s annual Product Responsibility Summit has brought experts together from within and outside the industry to discuss the issue.

“More than anything, take the time. Now,” says Brenner. “We’re in the ramp-up before it gets to be where every product is examined for PFAS. Understand where, what and which of your products has some PFAS chemicals in them. Take the time to investigate.”

Khattak is the senior digital editor at PPAI.